研究内容

(English version below)

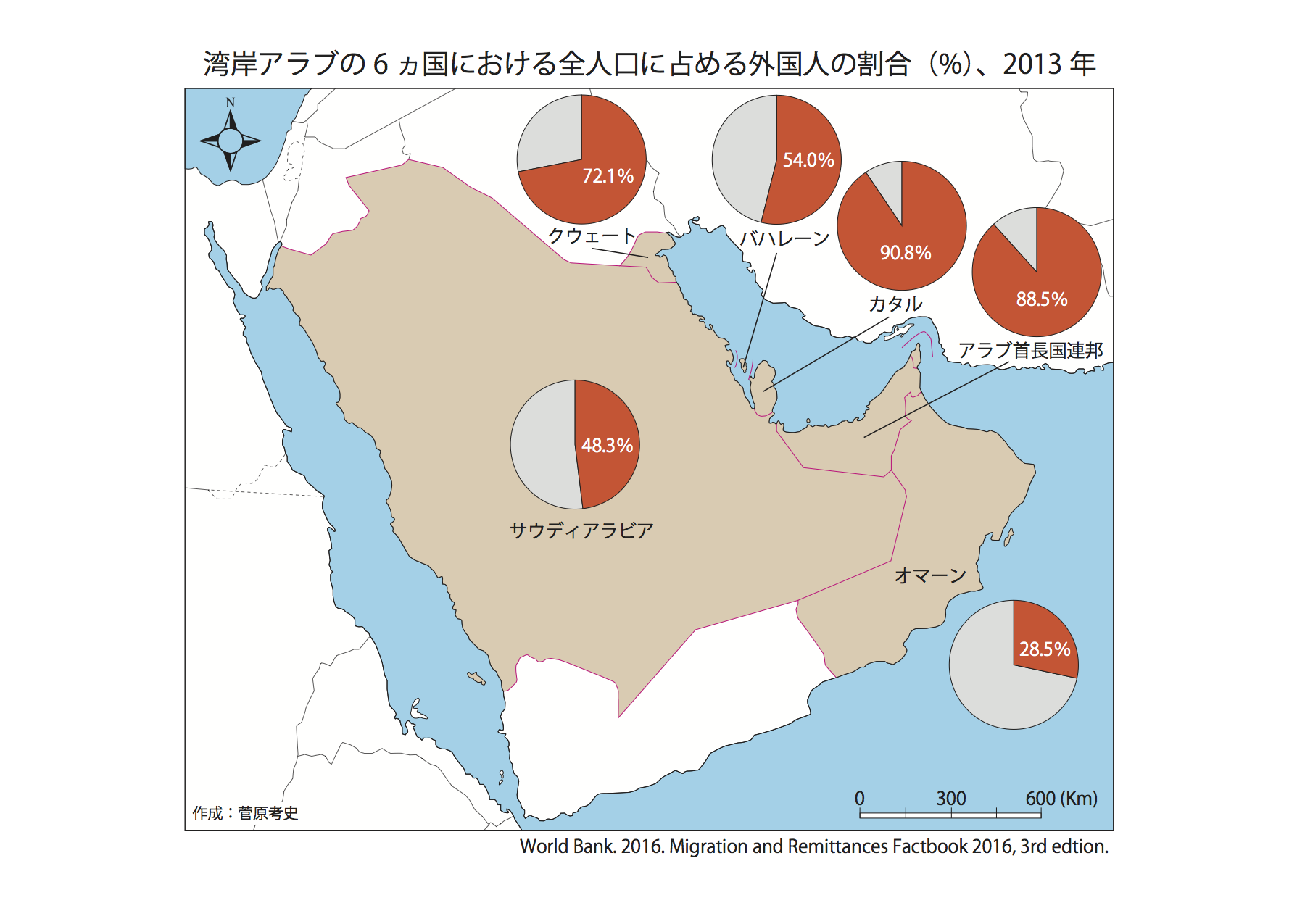

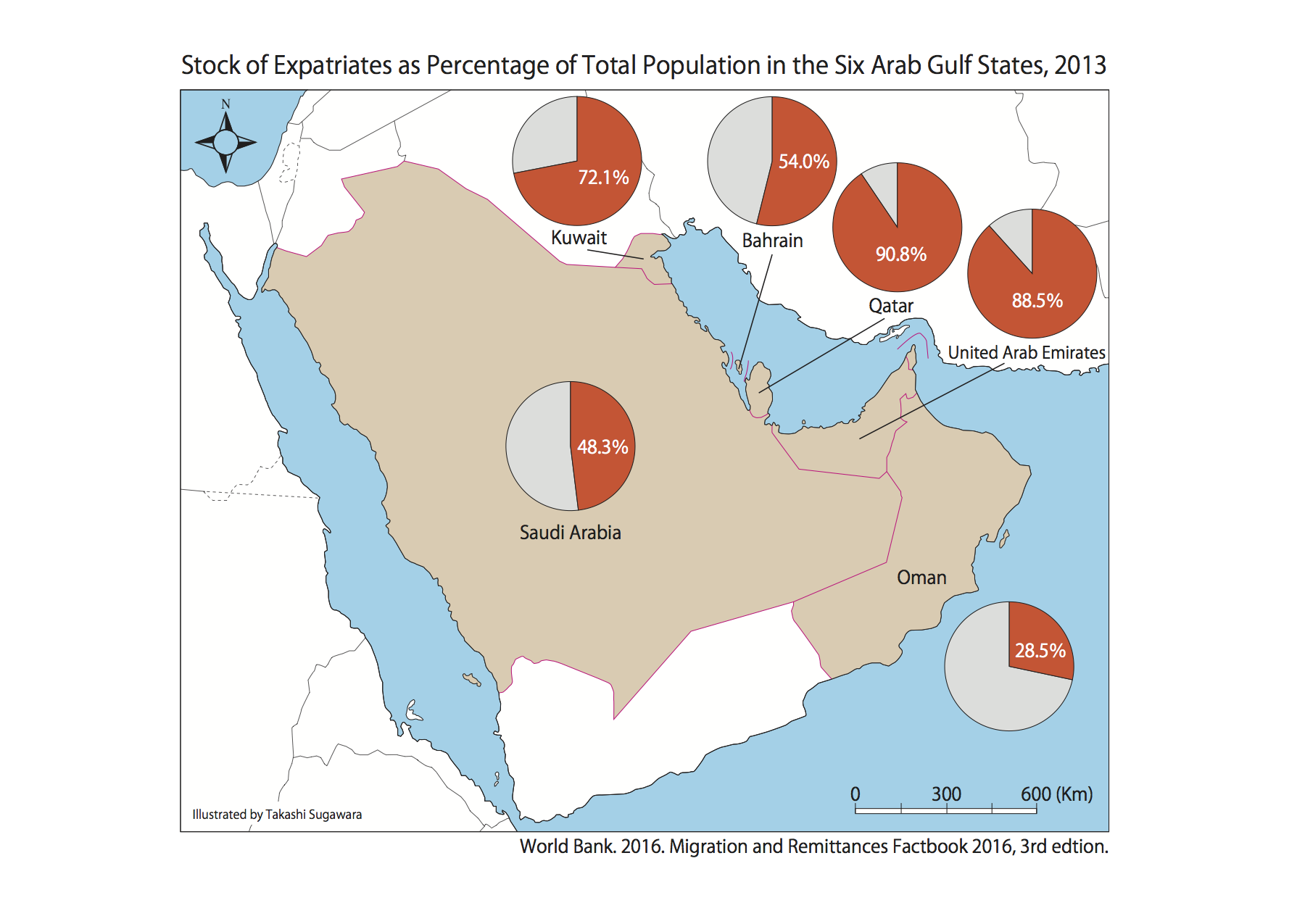

湾岸アラブ諸国はバハレーン、クウェイト、カタル、オマーン、サウディアラビア、アラブ首長国連邦(UAE)の6カ国からなる地域です。ここは、世界銀行による統計で2900万人の移民を受け入れており、北米、欧州とならんで、世界の三大移民受け入れ地域の一つです。また、総人口に占める移民の割合に注目した場合、湾岸アラブ諸国はその人口の56%が移民であり、世界一、移民の割合が高い地域となっています(図参照)。この地域は、世界でもまれな「多外国人国家」と呼ぶことができるでしょう。

湾岸アラブ諸国のもう一つの特徴として、移民のほとんどが一時的な滞在者であることが挙げられます。自国民と国際結婚した外国人など少数の人を除けば、外国人は2年程度の短期契約雇用の一時的労働者か、その家族です。契約が更新されなかったり、契約途中で解雇されたりした場合、すぐに家族とともに国を去らなければなりません。移民の定住を拒む湾岸アラブ諸国において外国人がシティズンシップを得られる可能性は皆無に近い状態です。

しかし現実には、湾岸アラブ諸国内に生活の基盤を築き、短期契約を更新し続け長期に滞在をする「長期一時滞在者」も多くなっています。一時的労働者の3割程度を占める専門職者や技術者には家族の同伴が認められるので、その結果、この地域で生まれ育つ移民二世も多いのです。

本研究は、こうした背景を持つ、湾岸アラブ諸国在住のアジア系移民二世の帰属意識について調査をします。かれらは、ホスト社会に包摂されないまま、国籍や民族ごとに分断された外国人コミュニティ内で育ちます。公立学校には入れないため、外国(欧米、インド、フィリピンなど)のカリキュラムの私立学校で学びます。また、コミュニティや学校から一歩出ると、世界各地のブランド製品や食品であふれるグローバル公共空間が広がっており、アラビア語ではなく英語で周囲の人たちとコミュニケーションをとります。一方、かれらは家族と一緒に親の出身国、つまり国籍上の本国にたびたび帰省していますが、湾岸アラブ諸国と比べると治安も生活環境も悪い本国に長期滞在しようとした場合、うまく適応できないケースが少なくありません。

したがって、かれらの多くは、同一の国籍や民族でまとまる移民コミュニティには愛着を感じていますが、シティズンシップ取得の見込みのない滞在国も、治安や生活環境が悪いうえに社会保障も十分整っていない本国も、最終的な居場所とは考えていません。かれらの教育やキャリアについての戦略は、第三国での将来的な居場所確保に向けて立てられるのです。

専門職などいわゆる「高度人材」への優遇措置として、外国からの一時的労働者の家族同伴を認めるケースは世界的に増えています。国際競争力を維持するために不足する労働力を一時的労働者で補おうとする政策は、日本を含む他の先進国や中進国でも今後いっそう増えると予想されています。本研究は、湾岸アラブ諸国だけでなく、外国人が一時的身分のまま長期滞在できる政策を検討する他の国々にとっても、その社会の将来像を見定めるうえで重要な参照例となるでしょう。

(English version)

The Arab Gulf states (referring to the six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council) comprise Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). As reported in recent World Bank statistics (see the chart below), these six states accept 29 million migrant workers in total and makes them the third major migrant destination of the world, following Europe and North America. Taking notice on the proportion of migrants to the total population of the Arab Gulf states, more than half of their population (56%) now are made up migrants.

The six Arab Gulf states have provided their migrant populations with a range of infrastructural facilities: from furnishing low-end apartments; shopping malls; parks and public transportations partly. Still, a large number of these migrants live in highly segregated environments with divisions based according to nationality, ethnicity and economic strata. Unless they were intermarried or have some social activities in common, they would have little chances of intermingling with other nationalities outside of their worksite. This is more so with their children whose life worlds can be limited between home and school.

Another defining feature is that almost all migrants in the Arab Gulf states are temporary residents. With a few exceptions such as investors, certain categories of specialists, and those who married with the male nationals, foreigners are temporary workers with short term contract employment of about two years. Moreover, if the contract is not renewed or if they are dismissed in the middle of their term, they must leave the country with their family at once. Thus, there is almost no possibility that foreigners can acquire citizenship (or permanent residency) in the Arab Gulf states. In the meanwhile, because these states allow professional workers and/or workers with middle to high income to sponsor family members, some middle-class workers bring their family and stay semi-permanently in the Gulf, though they remain as temporary workers and their dependents.

In this research, we will investigate ‘notions of belongings’ and experiences concerned with rootedness among the second generation Asian Gulf migrants (SAGM). These SAGM are brought up by being marked as foreigners and segregated by nationality and ethnicity, with little relationship with the nationals or being meaningfully included in the host society. Since they are not admitted to the public schools, they study at private schools following the curricula of foreign countries (Western, Indian, Philippine etc.). However, in an interesting twist, the classmates they encounter at these schools are multinational, and this is where the second generation forms new connections and future prospects that are different from those of the first generation.

These SAGM generally speak English fluently, rather than Arabic, partly reflecting the fact that many Arab Gulf cities are transforming themselves from being oil dependent economies to global cities and turning themselves into global hubs of higher education, finance and tourism. Furthermore, they grow up surrounded with globally-known brand products and foods coming from around the world. Many SAGM feel at home within migrant communities of their respective nationality and ethnicity. Nevertheless, neither their country of residence that is unwilling to provide citizenship, nor the parents’ country of origin (country of their passport) where they find security and living conditions are far too poor and social security is underdeveloped, are attractive to many of them as the countries they want to live eventually. Accordingly, their educational and career strategies are set for acquiring ways to immigrate to third countries where they can possibly be citizens and lead comfortable and peaceful lives.

There’s a new global trend of selective migrant policies in labor-receiving countries like US and in Europe, favoring highly skilled workers. Yet we shouldn’t forget that we are also living in an era that countries are being selected by these workers. Little studies have investigated how migrants select countries for their work and settlement. Nowadays, in order to maintain global competitiveness, an increasing number of middle- and high-income countries worldwide including Japan are eyeing to invite more professional and skilled migrant workers from outside. Some of these countries provide professional migrants with special privileges such the permission to bring their families so that they can live longer term and with social lives. Findings from this research will be an important reference point not only limited to cases of the Arab Gulf states, but also to any country which try to accept migrant workers on a temporary basis but with some measures to keep them long-term, by showing concrete examples of what will be social and cultural outcomes of such migrant labor policies.